SPRING ISSUE 2025:

April 21, 2025

The Art of Resistance: How Political Artwork Has Shaped America and Beyond

From the revolutionary engravings of the 18th century to the vibrant street murals of today, political artwork has played a pivotal role in shaping public opinion and influencing societal change. This article explores the power of visual expression in American history, highlighting key artists, movements, and the undeniable impact of LGBTQ political art. As artists continue to challenge oppression and mold the political landscape, their work remains a driving force behind progress and reform.

By David Radinoff

USE ARROWS TO MOVE THROUGH IMAGES

Political artwork has long served as a powerful means of shaping public opinion, sparking debate, and challenging authority. Throughout history, artists have used their work to comment on social injustices, war, government policies, and movements for change. In the United States, political art has played a crucial role in reflecting and influencing the nation's political climate, while internationally, similar artistic expressions have shaped revolutionary movements and ideological battles. From early American protest engravings to contemporary street murals, political artwork has evolved as both a tool of dissent and a reflection of collective consciousness.

The roots of political artwork in the United States can be traced back to the 18th century when artists used prints and illustrations to critique British rule. One of the most famous early examples is Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving, The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King Street. This depiction of the Boston Massacre was heavily propagandized, exaggerating British aggression to rally colonial opposition to British rule. Such engravings played a critical role in fostering revolutionary sentiment, illustrating the power of visual media in shaping political perspectives.

As the 19th century progressed, political artwork became a staple in newspapers and periodicals. The rise of lithography allowed for mass-produced political cartoons, and no figure was more prominent in this realm than Thomas Nast. His satirical illustrations for Harper’s Weekly in the 1860s and 1870s targeted political corruption, most notably through his depictions of Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed. Nast’s work was instrumental in exposing governmental fraud and is credited with influencing public opinion to demand reforms. Moreover, his imagery helped define enduring political symbols, such as the Democratic donkey and Republican elephant, which remain in use today.

Image 1: Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving, The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King Street, Image 2: I’m Still Here by Jean Michel Basquiat, Image 3: Uncle Sam Caricature By Thomas Nast Political Cartoon 1877

The early 20th century saw an expansion of political artwork as the country grappled with issues like workers' rights, war, and civil rights. During the Great Depression, artists working under the Works Progress Administration (WPA) created murals and posters that depicted American resilience and the struggles of laborers. These works, while often government-commissioned, carried strong messages about economic disparity and the dignity of work. At the same time, printmakers such as José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera, although based in Mexico, influenced American artists through their bold depictions of revolutionary ideals and class struggles.

During World War II, political artwork became a key element of propaganda efforts on both sides of the conflict. In the United States, the government employed artists like Norman Rockwell to create patriotic images that encouraged support for the war effort. Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series, inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 speech, depicted core American values and was widely circulated to boost morale. Meanwhile, posters such as Rosie the Riveter became iconic representations of women’s contributions to the war industry. The use of art as propaganda was not unique to the United States—Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and other nations relied heavily on state-sponsored political artwork to promote their respective ideologies.

The 1960s and 1970s marked a radical shift in political artwork as movements for civil rights, feminism, and anti-war activism took center stage. Artists like Emory Douglas, the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, created striking graphic designs that called for racial justice and liberation. His bold, high-contrast images of Black empowerment were widely distributed in the Black Panther newspaper, making his work one of the most recognizable visual components of the movement. Similarly, artists protesting the Vietnam War produced anti-war posters, often using bright colors and psychedelic aesthetics to convey their messages. Peter Max’s vibrant, countercultural imagery and the anti-war works of the collective Guerrilla Girls exemplified how political artwork could challenge mainstream narratives and mobilize activists.

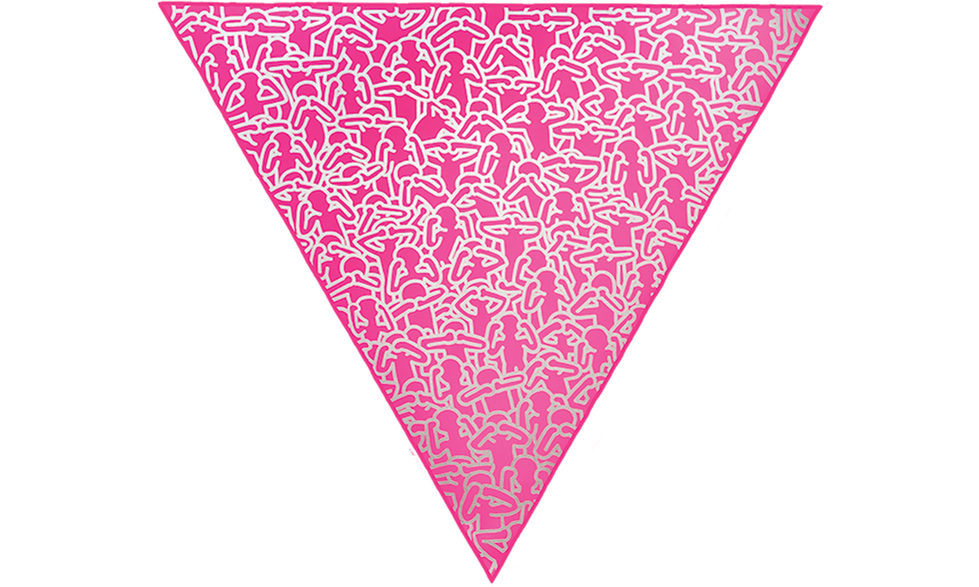

Image 1 and 2: Death = Silence Series and Pink Triangle By Keith Haring, Image 3: Revolution in Our Time by Emory Douglas

The latter half of the 20th century also saw the rise of graffiti and street art as potent political tools. Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring used the streets of New York City as their canvas, addressing issues of racism, AIDS, LGBTQ rights, and economic disparity through their distinctive styles. Haring, in particular, was known for his advocacy for LGBTQ visibility and AIDS awareness through his bold and accessible imagery. Banksy, the anonymous British street artist, followed in their footsteps, creating provocative stencil-based artwork that critiques capitalism, war, and government surveillance. His works, often appearing overnight on city walls, demonstrate how political artwork continues to thrive outside traditional gallery spaces.

In contemporary America, political artwork remains as influential as ever, particularly in response to social movements such as Black Lives Matter, climate activism, LGBTQ rights, and immigration rights. Murals commemorating George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other victims of police violence have appeared across the country, turning public spaces into powerful platforms for advocacy. Artists like Shepard Fairey, best known for his Hope poster of Barack Obama, continue to create imagery that defines political moments and shapes public discourse. The digital age has further expanded the reach of political artwork, allowing memes, digital illustrations, and viral graphics to influence millions within hours of their creation. LGBTQ political art has played a particularly vital role in advocating for equality and visibility, from the rainbow flag designed by Gilbert Baker to contemporary murals and posters addressing transgender rights and inclusivity.

While the United States has a rich history of political artwork, it is by no means unique in its use of visual art as a means of resistance and commentary. In France, the political posters of the 1968 student protests were instrumental in rallying demonstrators against government repression. In China, the Cultural Revolution saw an explosion of propaganda art used to glorify Mao Zedong and communist ideology. More recently, the Arab Spring uprisings were accompanied by graffiti and murals that expressed the frustrations and hopes of protesters fighting for democracy.

The power of political artwork lies in its ability to communicate complex ideas in an immediate and visceral way. Unlike speeches or essays, which require time to process, a single image can convey a message instantly, making it a uniquely effective form of activism. Throughout American history, political artwork has been a mirror reflecting societal struggles, a hammer breaking down oppression, and a beacon illuminating paths toward change. Artists do not merely document history; they shape it, influencing public sentiment and even helping to mold laws and policies. As long as there are voices to be heard and injustices to be challenged, political artwork will continue to serve as a potent force in shaping the political landscape.

----

M

About the author

David has a passion for writing that centers queer issues, culture, and the nuances of personal identity. With a background in both journalism and creative writing, his work spans a wide range of topics, including the complexities of identity, the intricacies of relationships. He has contributed to numerous online publications and print outlets, providing thought-provoking essays that explore the intersections of pop culture, social justice, and LGBTQ+ advocacy.

Since 2004, METROMODE has been a beacon for the LGBTQIA+ community and our allies. We’re a publication built on quality, not only in our advertising clients but in the look, feel, and editorial pieces of each magazine. METROMODE speaks to the entire community with thoughtful analysis of local, national, and global events affecting our community; developments in business, finance, the economy, and real estate; interviews with emerging and seasoned artists, musicians, and writers; appealing new opportunities to enjoy Colorado’s rich culture and social atmosphere; quality aesthetic experiences from film, to food, to music, to art, to night life; and challenging social and political thought.

MORE FROM METROMODE

CONNECT WITH US

© 2024-2025 METROMODE magazine. All rights reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our User Agreement and Privacy Policy and Cookie Statement. METROMODE magazine may earn a portion of sales from products that are purchased through our site as part of our Affiliate Partnerships with retailers. The material on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, except with the prior written permission of Metromode magazine.